If you scroll beyond the dance videos and Vine-like sketches on TikTok, you’ll probably come across some content that goes deeper. The algorithm is so good it might even hurt you where it hurts. It could be a therapist stirring tea while she gives advice for insomnia or a spiritual guru practicing reiki healing through the screen. Instagram creators provide guidance too, posting text and drawings accompanied by lengthy captions with relationship advice or ways to heal the inner child.

This begs the question, Where do we go when things get tough? The trend of social media transcending entertainment suggests that when we need someone to lean on, we may find answers in the same place we go to watch a funny cat video – our social channels. Besides those using the platforms to share wisdom, creators post about their own mental health journeys as a way to relate and find support.

This type of psychological content rose to popularity during Covid lockdowns, as a reflection of the publics’ collective mental health challenges, along with a movement to destigmatize mental health – one that began even before the pandemic. #MentalHealth has 17.5 billion views on TikTok and 33.3 million posts on Instagram.

@i.dan.ya Day 1 of trying to find myself again #mentalhealthmatters #zillennial

♬ Back In Your Life (Instrumental) - Track and Field

TikTok user @i.dan.ya shares her mental health journey and ways she is showing up for herself. TikTok is known for this raw, relatable content.

The irony that users are finding mental health guidance on platforms constantly slammed for damaging mental health is not beyond me, and it’s not beyond these platforms either, as they have started and will continue to roll out changes in support of mental health advocacy, following extreme backlash.

Facebook, owner of Instagram, was put through the wringer after the Wall Street Journal reported that the company was aware of the negative effect Instagram was having on teen girls’ mental health, and did little to combat it.(1) Internal research and presentations given to Facebook execs, including Mark Zuckerberg in 2020, show a deep dive into Instagram’s mental health effects, with one slide titled “Teens who struggle with mental health say Instagram makes it worse.” When Senators Richard Blumenthal and Marsha Blackburn asked Instagram to release their findings, they responded that the research had not reached a consensus on Instagram’s impact on mental health.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Sen. Blumenthal said in an email, “Facebook seems to be taking a page from the textbook of Big Tobacco – targeting teens with potentially dangerous products while masking the science in public.”

Karina Newton, Instagram’s head of public policy, wrote in a blog post following the scandal, “Social media isn’t inherently good or bad for people. Many find it helpful one day, and problematic the next. What seems to matter most is how people use social media, and their state of mind when they use it.” (2)

In the post, she says that Instagram will take actions to help users protect themselves from bullying, connect people with local support organizations, and provide nudges away from certain content that promotes social comparison for users that seem to be dwelling on it. Newton acknowledges that Instagram has been used as a platform for social comparison, saying, “We’re cautiously optimistic that these nudges will help point people towards content that inspires and uplifts them, and to a larger extent, will shift the part of Instagram’s culture that focuses on how people look.”

A Facebook Groups ad shows the platform being used to answer a woman’s question, “Feeling lost…help?”

Even before this most recent surge of media backlash, Facebook released an advertisement for Facebook Groups that positioned Groups as a community-building and helpful tool for young people. The ad further confirms the pressure social media platforms are feeling to answer society’s questions about social media’s effects on us IRL. In the ad, a young woman asks her Facebook Group, “Feeling lost…help?” and they rally around her with advice that inspires her to try yoga, talk to people who feel lost, too, and go to a pool party.

Just hours after Wall Street Journal’s Instagram article was released, TikTok (probably anticipating the shitstorm to come) announced their new mental health initiatives. (3) In the written announcement, they lean into the fact that their platform has become a source of mental health guidance, saying, “We’re inspired by how our community openly, honestly and creatively shares about important issues such as mental well-being or body image, and how they lift each other up and lend help during difficult times.”

In addition to TikTok’s mental health guides, when a user searches words related to an eating disorder, they will be prompted with suggested tools and resources. When a user searches about suicide, they are directed to the Crisis Text Line and can opt-in to see videos created with the guidance of mental health professionals.

If social media is like big tobacco, TikTok has released a sort of “Surgeon General’s Warning” on certain content. PSAs have been placed on certain hashtags like #WhatIEatInADay, they’ve inserted an opt-in step to see other content that TikTok has deemed potentially distressing. These videos will not show up on anyone’s main feed, the For You Page.

Other platforms like Twitter and Youtube are chiming in too, with Twitter releasing a new “Safety Mode” feature and YouTube’s CEO remarking that the mental health resources available on YouTube make it “valuable” for teens’ mental health. (3,4)

As people continue to turn to social media for emotional support, we could see data mining being used to detect people with high-risk behavior and mental health conditions and provide them resources, and to help researchers understand certain demographics and geography that correlate with mental health. (5) We’re all aware of the amount of data Facebook and other platforms have on us, down to the subtlest details. So it’s no surprise that, HIPAA-willing, the platform could provide insight into the mental health of its users even before their own therapists. It would also entail that they would have to sign over their user information to researchers, which probably won’t happen anytime soon. (6)

Studies have also shown a duality in the mental health effects of social media, confirming Instagram’s sentiment that the platforms aren’t inherently good or bad. A study published in the Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science found that social media’s benefits and challenges were narrowed down to the following. (7)

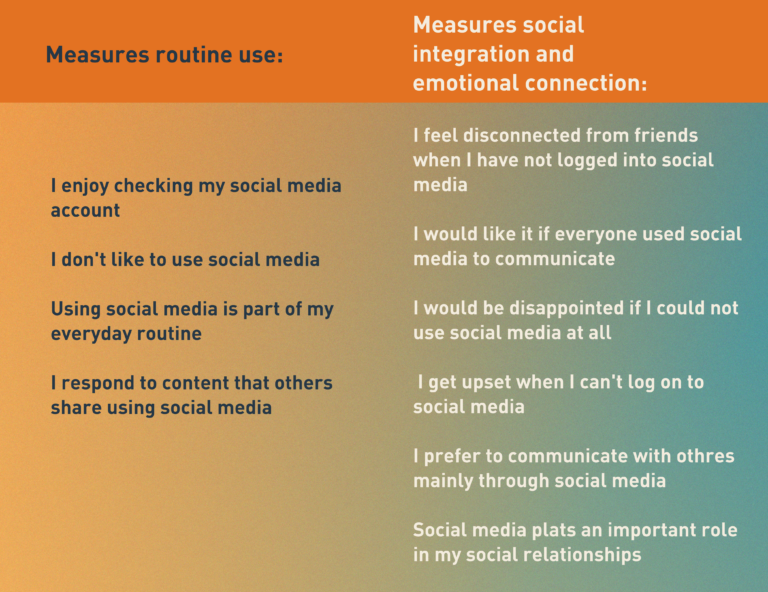

Further, a study by Harvard Researchers found that routine social media use led to positive mental health outcomes, but users that had an emotional connection to social media experienced negative mental health outcomes.(8) It had less to do with how often or how long people use social media, but the way users engaged emotionally. It goes on to say, “Existing literature on the link between social media use and health is equivocal and inconclusive and often does not acknowledge the increasing integration of social media use into users’ social behavior nor the emotional connection that it generates.”

Here’s the way routine vs. emotionally connected use was measured, on a scale of strongly disagree to strongly agree:

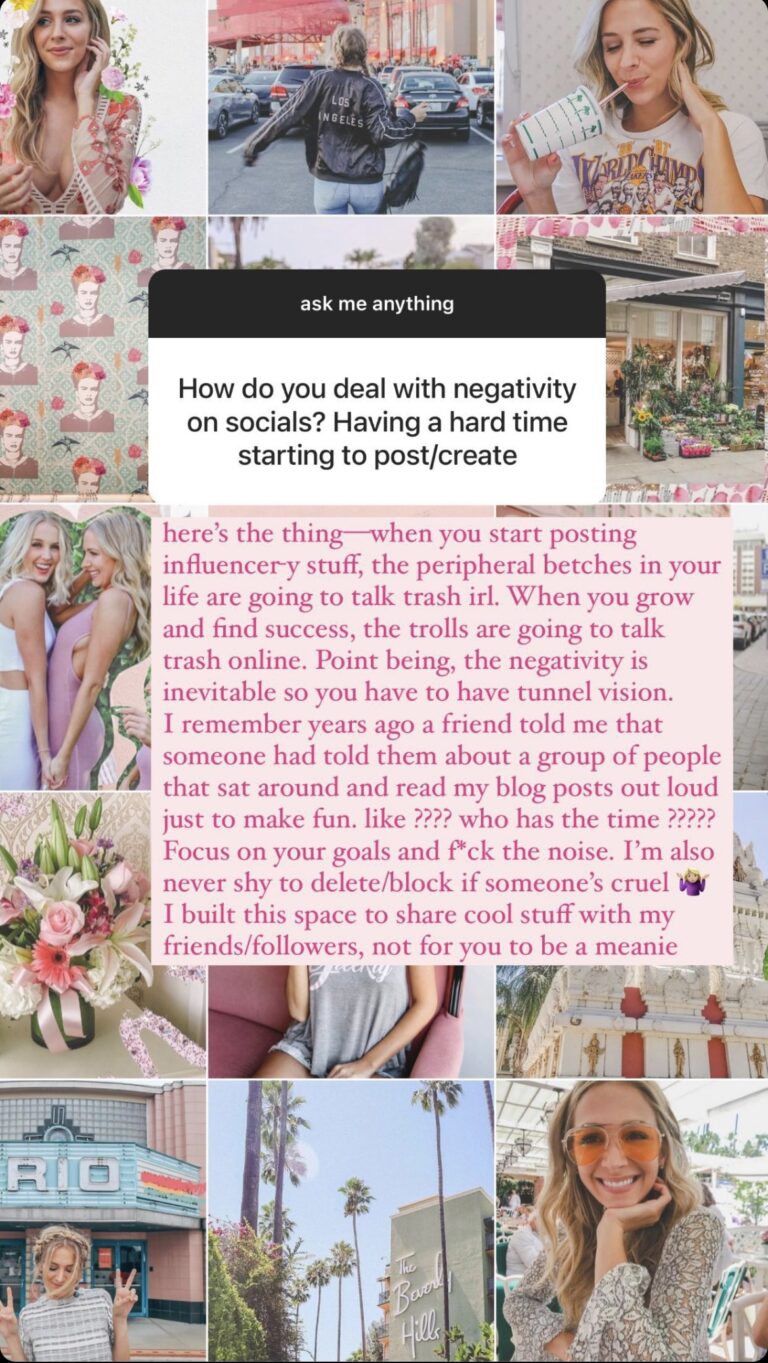

Instagram content creator, @talliia, shares advice for dealing with negativity on social media.

Social media’s effects are just as nuanced as our “real life” human relationships. But one thing is certain – because social media does carry an emotional weight for many, it is inextricably linked with mental health and this isn’t a notion that will blow over.

I can’t help but wonder if the mental health content on social media is sort of like hosting an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting at a bar. What is the reckoning between mental health support in a place that can cause isolation, addiction, and social comparison?

In regards to the mental health effects of social, some argue that it’s a case of the chicken and the egg. Mental health problems could be caused by social media, or mental health problems could affect how people use social media. Chicken or egg, nothing negates the responsibility the platforms and the players who use them carry.

Are disclaimers and links to more resources and the removal of like counts enough to fix the problem? For now, it may appease those concerned, but I see platforms moving in a more decisive direction in the future. As the public conversation around mental health and social media unfolds, I wouldn’t be surprised if more restrictions designed to protect mental health are put in place for advertisers, especially those marketing to younger audiences.

It seems most of the platforms are a step behind, constantly receiving flack for providing little to no response to what some consider a public health crisis until nudged by some outside force like the Wall Street Journal. Given the recent heat they’ve received, I expect to see the platforms responding in more conclusive ways. This could include new features that encourage positive interactions between users, stricter guidelines for advertisers, and more transparent research provided by the platforms.

If the platforms themselves don’t implement guidelines, it is up to marketers to put up their own guardrails against content that may be damaging to the psyche of their audiences. The clients they are representing don’t want to be caught in the mess, either.

Advertisers will also need to consider how their content is perceived on a platform that is now a source of both mental health guidance and detriment. The onslaught of negative press about social media combined with the real mental health effects felt especially by our younger audiences will change the attitudes people have towards the content they see on these channels.

According to a recent poll by Ad Age and The Harris Poll, 55 percent of people agreed brands and organizations should stop advertising on Facebook. 78 percent said brands should be concerned about ads appearing next to negative content on websites or apps, and 54 percent said they associate a brand with the unrelated content surrounding ads on social media and sites. However, 62 percent of users said it was unlikely they would delete the app themselves. (9) Sound a bit like Social Media Stockholm Syndrome?

While they still aren’t closing the door on the platforms, social media users have a decreasing tolerance for toxicity. And they may not associate social media with pure entertainment. In fact, they might be a bit wary.

Marriage and family therapist Vienna Pharaon (@mindfulmft) uses her Instagram platform to share relationship advice.

It seems that people of all ages these days can relate to a certain degree of addiction to their phones and social channels. The struggle of distraction and learning to break away from your phone is a popular subject of conversation and literature, as is muting or unfollowing those that don’t add value to your social media experience. If you scroll on TikTok long enough, the platform is even designed to have a video pop up where some guy tells you to take a little break from the phone.

As evidenced above, although people are fed up with the negative aspects of social media, they aren’t necessarily leaving the platforms for good. As long as there is an audience, brands don’t need to leave either. They have an opportunity to further this movement towards less emotional connectivity to social media, more good “real life” interactions and creating a healthier online environment, overall. Users are already taking it upon themselves to better their social media environment, and marketers should too.

“I hate it here” is a phrase seen often on social media channels, reflecting the sentiment people have towards social media, despite its widespread popularity. The definition above is from Urban Dictionary.

It’s probably obvious to consider if your ads are reinforcing unhealthy beauty standards or if our comment section is always volatile.

But ensuring that your content is not toxic is only the first step. Think of it like this, not toxic ≠ healthy. People want to feel like they are being responsible with their mental health and probably worry that social media is doing more harm than good for their headspace.

So the next step is to understand and align with those conflicting feelings about social media, the guilt one may feel for using it, and try to encourage social media use that works with, not against, our mental health. One, because that’s the right thing to do, and two, because that’s what people really want out of social media. It’s time to acknowledge those funny feelings.

Here’s an example – it’s probably fair to assume that a large portion of your audience is probably scrolling on their phone while your TV ad plays. Picture an ad from a pizza place that straight-away tells you to put that phone to use – order a pizza, call some friends to come over, then put the phone away, and have a fun night surrounded by people close to you.

Or an ad for just about anything that offers a break in the news feed. Maybe it’s simply a break to pause, with a prompt to breathe in and out while you check out a minute-long video of a waterfall. Show consumers you care about how social media makes them feel and that you hope to make that a more positive experience.

@spicy_mama_geeta Go out (safely) and have fun! #spicygang

♬ original sound - Geeta Upadhyaya

TikTok user @spicy_mama_geeter urges viewers to get outside and take a walk.

As marketers, we are the ones financially upholding these institutions. Whether you see it as a responsibility or an opportunity, we have the power to enact positive change in these platforms. Since we are paying for space in this strange environment, we might as well paint some murals on the walls. After all, a lot of people are meeting us there, so we should do them right.

Works Cited

- Wells, Georgia, et al. “Facebook Knows Instagram Is Toxic for Teen Girls, Company Documents Show.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 14 Sept. 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-instagram-is-toxic-for-teen-girls-company-documents-show-11631620739.

- Newton, Karina. “Social Media and Well-Being: Instagram’s Research and Actions: Instagram Blog.” Instagram, Instagram, 14 Sept. 2021, https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/using-research-to-improve-your-experience.

- Hatmaker, Taylor. “Twitter Is Testing a New Anti-Abuse Feature Called ‘Safety Mode’.” TechCrunch, TechCrunch, 1 Sept. 2021, https://techcrunch.com/2021/09/01/twitter-safety-mode-harassment/.

- Grant, Nico, and Emily Chang. “YouTube CEO Says Platform Is ‘Valuable’ for Teens’ Mental Health.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 27 Sept. 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-09-27/youtube-ceo-says-platform-is-valuable-for-teens-mental-health-ku30qkkd

- Wadhwa, Tara. “New Resources to Support Our Community’s Well-Being.” TikTok Newsroom, TikTok, 14 Sept. 2021, https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/new-resources-to-support-well-being.

- Kopel, Rotem. “Mining Social Media Reveals Mental Health Trends and Helps Prevent Self-Harm.” Scientific American, Scientific American, 14 Sept. 2021, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mining-social-media-reveals-mental-health-trends-and-helps-prevent-self-harm/.

- Kulkarni, Param. “Apply Hipaa to Help Facebook Transform Mental Health for Good.” STAT, 12 Oct. 2021, https://www.statnews.com/2021/10/13/apply-hipaa-facebook-transform-mental-health-for-good/.

- Naslund, John A., et al. “Social Media and Mental Health: Benefits, Risks, and Opportunities for Research and Practice.” Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, vol. 5, no. 3, 20 Apr. 2020, pp. 245–257., https://doi.org/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41347-020-00134-x.

- Sloane, Garett. “Facebook Users Unlikely to Delete App but Want Brands to Pull Ads, Poll Finds.” Ad Age, 11 Oct. 2021, https://adage.com/article/digital-marketing-ad-tech-news/facebook-users-unlikely-delete-app-want-brands-pull-ads/2371791.